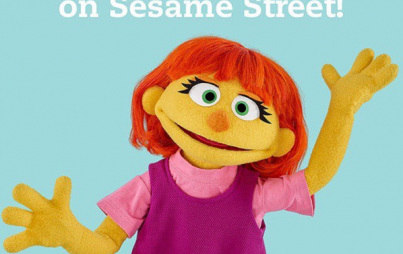

Image via Sesame Street

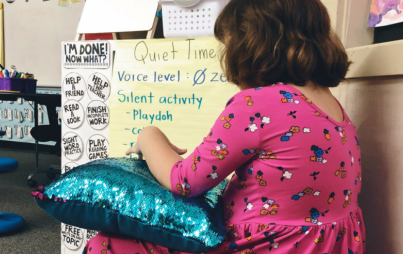

My daughter, like Julia the muppet, doesn't always look at you when you talk to her. She hides behind me, or her hair, or maybe even under a chair.

Not that long ago, I read with interest a blog post by Autism Daddy that revealed his super secret job at Sesame Street and the show's plans to create an autism outreach initiative. Since another autism parent was intimately involved with the project, and let's face it because it's Sesame Street, I assumed that it would be awesome. But, when I opened Twitter this morning and saw a feed full of a little autistic muppet named Julia, I cried.

It took five years for my daughter to be diagnosed with autism. There were dozens of red flags, beginning from the time she was about 10 months old, but her pediatrician always told me that she was fine. "She made eye contact with me," she reassured me. "She can't be on the spectrum." Besides, most children with autism, she reminded me, are boys.

When I tell people our story, they are often shocked. My daughter is not a quirky kid who struggles to make friends — her autism is obvious to even a slightly interested observer, and that becomes more true the older she gets. These days, if I do not tell people that she is autistic, they give me meaningful looks and ask pointed questions until I finally give in and tell them that she has autism.

What most people don't realize is that our experience isn't rare. It can be challenging for any parent to get an appropriate autism evaluation and diagnosis for their child, but it can be almost impossible when your autistic child happens to be a girl.

Although 1 in 68 children has autism, boys are five times more likely to be affected than girls; autism affects 1 in 42 boys, compared to 1 in 189 girls. While there is some debate about whether this is entirely due to a difference in gender prevalence or diagnostic inequity, it's safe to say that dramatically fewer girls have autism than boys. And, as a result, autistic girls are often overlooked.

The day that my daughter was finally diagnosed with autism, I cried the entire way home. She was in the backseat of the car, chatting away happily, and I answered her in cheerful monosyllables, but inside my heart was breaking. I didn't know what to expect, or what to do, and I was overwhelmed by my fear and confusion — and even grief.

There is no roadmap for autism. Symptoms come and go, and challenges ebb and flow seemingly at random. Sometimes, my daughter seeks out sensory input, leaping and crashing with wild, dangerous abandon, and sometimes she covers her ears and cowers in sensory pain at the sound of the oven timer from two rooms away. Her tolerance is like a cup that overflows and spills out everywhere when it's too full, but she is both the only one who knows when she is nearing her limit and the only one who can't always communicate her limits.

My daughter, like Julia the muppet, doesn't always look at you when you talk to her. She hides behind me, or her hair, or maybe even under a chair. When children ask her to play with them, she often screams... just a little. Usually, she begins to feel comfortable enough to join in the fun right about when it's time to leave. Our family and friends know my daughter's challenges and they love her in spite of, and even because of them. But strangers, kids at school, and that slightly annoying kid down the street do not. They assume that she thinks and reacts like they do, and when she turns away or screams, they think that means that she doesn't want to play.

Children who grow up with Julia on Sesame Street will not need to ask what is "wrong" with my daughter, or even what autism is. They will understand it from the time they are tiny, and that understanding will inform and influence their perspective even as they become adults. They will know that some people are different, and what autistic differences can look like, and they will be kinder and more empathetic for having learned it.

Parents will also benefit from the comprehensive resources that Sesame Street has compiled. Even though we know that early intervention in autism can actually re-wire the brain and improve long-term results, our delay in diagnosis prevented my daughter from receiving early intervention services. That may change for parents who become more familiar with the signs and symptoms of autism, and even the idea that girls can have autism, too. Plus, as any autism parent knows, social stories and videos can be lifesavers and combining them with the magic that is Sesame Street is even better.

A few months ago, I decided to order a few children's books about autism for my daughter and her siblings. I wanted to help my other young children better understand autism and how it makes my daughter different, but I also wanted books written for children with autism themselves. As we read the books together, and I watched as my daughter began to light up at the idea of autism being different and special, I realized that nowhere in those books was a girl who loves cats, art, and everything that glitters and sparkles — in fact, there were no autistic girls at all. Every single autistic child in every single book was a boy.

What Julia has given my daughter is the gift of representation. For the first time, she will not just see a child with autism in the media — she will see a girl with autism. She will come to see Julia as autistic, different, and yet the same, and she will begin to know that she, too, is autistic, different, and yet the same. It is a simple thing that means everything.