Be With Me Always by Randon Billings Noble

About the Book

“Be with me always—take any form—drive me mad! only do not leave me in this abyss, where I cannot find you!” Thus does Heathcliff beg his dead Cathy in Wuthering Heights. He wants to be haunted—he insists on it. Randon Billings Noble does too. Instead of exorcising the ghosts of her past, she hopes for their cold hands to knock at the window and to linger. Be with Me Always is a collection of essays that explore hauntedness by considering how the ghosts of our pasts cling to us.

In a way, all good essays are about the things that haunt us until we have somehow embraced or understood them. Here, Noble considers the ways she has been haunted—by a near-death experience, the gaze of a nude model, thoughts of widowhood, Anne Boleyn’s violent death, a book she can’t stop reading, a past lover who shadows her thoughts—in essays both pleasant and bitter, traditional and lyrical, and persistently evocative and unforgettable.

Erin Khar: Your essay collection explores all the ways in which we are haunted. Tell me a little bit about how the concept for the collection was conceived.

Randon Billings Noble: Hauntedness — or darker nostalgias — has always been a writerly preoccupation of mine.

At first, I didn’t know I was writing a book. I was just writing essays. But then I started to see some patterns in the themes and subjects of the essays — a long-ago lover who still shadows my thoughts, a book I keep rereading, places I keep returning to — and I realized that what binds much of my work is a kind of hauntedness.

I’m reluctant to relinquish the past, the road not taken, so I return to these other lives again and again.

So I kept writing with hauntedness in mind, and slowly the collection began to take shape. The essays are highly varied in subject matter — a near-death experience, a difficult twin pregnancy, Stonewall Jackson’s amputated arm, a somewhat surreal high school reunion, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, Michael Cunningham’s novel The Hours … But they all explore what was and what might have been and what might still be.

EK: You explore memory and story through the body. Do you have a process in place for accessing the stories stored in the body?

RBN: What a great question. I don’t – but now I want to!

I’ve always had a strange and somewhat distant relationship with my body. In “Mirror Glimpses,” I write that during my first year of college, I felt as if my body were just “a cup to carry around my brain.” But perhaps that’s what makes bodily issues so fascinating to me — and allows me the psychic distance to explore them with a certain degree of objectivity.

The only thing I can think of that I do in terms of process is that I walk a lot — sometimes deliberately in the mornings or if I’m stuck on a particular piece of writing, but also just to get around my city. In some ways, this is still just a way of getting my brain out in the world, but something happens while walking — and looking and sensing and thinking. I write about this in my essay “Camouflet,” in which I see myself as a kind of flâneuse, walking the streets of my own city as George Sand did in Paris and Virginia Woolf did in London. What do you see when you’re somewhat invisible moving through the world? Something different if you’re a flâneuse, I think.

EK: What are the books that shaped you as a person and as a writer?

RBN: When I was in fourth grade, I wanted to be a witch. But then I read Harriet the Spy and decided to be a spy instead. Then I grew up a little and realized that witch + spy = essayist.

Essayists are always observing, taking notes, creating stories and theories from what we’ve seen. And I think there’s a little witchcraft in essay writing.

Potentially strange ingredients are mixed together, a spell is cast, and the reader is — hopefully —transformed.

Later, individual essays had a profound influence on me. I read Joan Didion’s “Good-Bye to All That” when I was a graduate student in New York City. Like Didion, I, too, was very young and believed you could never stay too long at the fair. But I also saw how a kind of wisdom could be wrought from experience.

Then there was Cheryl Strayed’s “The Love of My Life” and its honesty without apology, Maxine Hone Kingston’s The Woman Warrior and the way it wove together myth and memory, Eva Saulitis’s fusion of science and poetry in Leaving Resurrection, and Claudia Rankine’s use of text and image in Citizen. All of these essays and collections helped shape me as a writer.

EK: What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received? What’s the worst?

RBN: The best wasn’t a piece of advice, per se, but a general idea: that of serious play. Playing is crucial to any creative activity. To some, that might sound frivolous. But serious play is play in service to your work. You fool around, experiment, romp, take risks, sometimes fall flat, but it’s all right — because it’s all play. A playful approach keeps you loose, and that’s when the odd thoughts, the swerves, have room to come through.

The worst is also an idea: that, in creative nonfiction, artistic truth is more important than factual truth. In my mind, the desire to express an artistic truth does not give the writer license to tamper with factual truth. An essay must have both. That’s both the beauty and challenge of the form. Anything else is cheating.

EK: What are you reading?

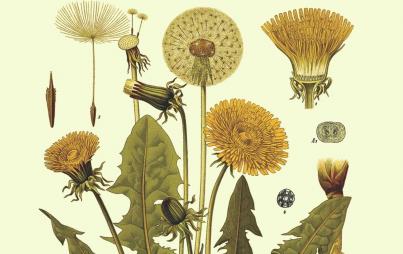

RBN: I’ve been putting together an independent study on essays on the edge of poetry. I have been (re)reading Anne Carson’s “The Glass Essay,” Mary Ruefle’s Madness, Rack and Honey, Lee Ann Roripaugh’s Dandarians, and Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights — all of which is, indeed, delightful!

Randon Billings Noble is an essayist. Her collection Be with Me Always was published by the University of Nebraska Press in 2019, and her lyric essay chapbook Devotional was published by Red Bird in 2017. Her work has been nominated for Pushcart Prizes, listed as Notable in The Best American Essays, and appeared in the Modern Love column of The New York Times, Brevity, Creative Nonfiction, Fourth Genre, and elsewhere. Currently, she is editing an anthology of lyric essays forthcoming from the University of Nebraska Press in 2021, and she is the founding editor of the online literary journal After the Art.