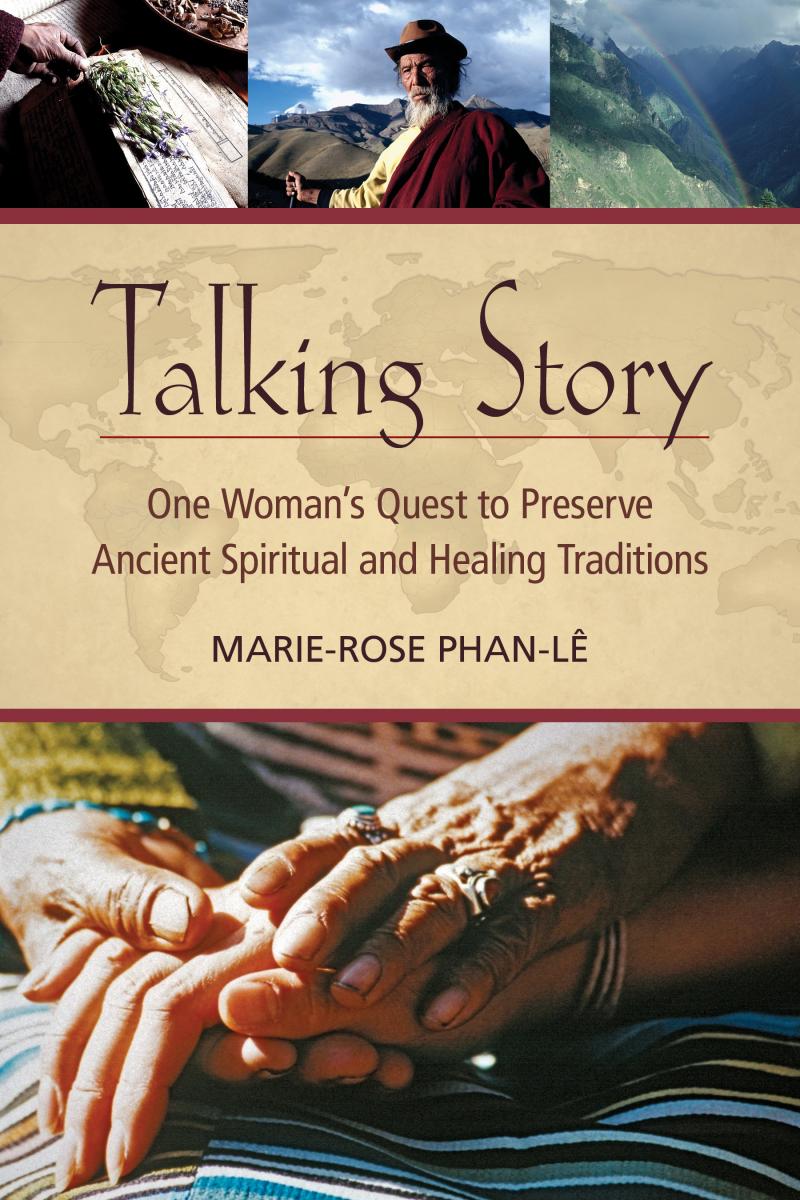

An apprentice healer born in Vietnam and educated in the west, Marie-Rose Phan-Lê serves as a thoughtful guide to the spiritual world in her acclaimed documentary Talking Story. That film took Phan-Lê from Hawaii and Eastern Peru to the Himalayas, India, China and beyond to explore the healing traditions of indigenous cultures around the world —traditions that have been threatened by the forces of habitat destruction, cultural assimilation and globalilazation.

Now, that quest has been turned into a tome, set for release by North Atlantic Books on Dec. 2, that's been described as "brave, brilliantly written and exhilarating" and a "wonderful bridge that spans across many cultures presenting an expanded view of healing and wellbeing.” Ravishly got a sneak peek of Phan-Lê's foray into shamanism, plant medicine, mysticism and divination, shared below. Like what you read? Order the book here.

***

In Hawaii, when an invitation is extended, the host or hostess will say, "Come over and let's talk story." Talking story is about taking the time to linger over the details of the mundane, to ponder the realms of the profound, and to surrender any structure of time or agenda. It is practicing the art of listening and of being present.

As I began production of the Talking Story documentary project, traveling from Hawaii to the Himalayas, it wasn't long before I realized that in order for me to access healing traditions and healers in remote areas of the world, I would have to practice talking story. There would be no hit-and-run interviews, no rigid film production schedules, no way to remain an anonymous gleaner of other people's wisdom and experiences. Talking story is about intimate connection—in order to earn the honor of hearing the stories of another, I had to be willing to reveal my own.

This posed quite a challenge for me, considering my background. I was born in Vietnam and spent some time in France before coming to the United States as a child. As with all well-assimilated immigrants, I was taught that survival depended on my ability to blend in. It's no wonder that the myth of the objective "documentarian," a scientist of sorts separated from her subjects by a veil of romance or a lens of scrutiny, was so appealing to me.

My plan to remain unseen didn't last long, for with most healers or spiritual leaders I wished to meet, I first had to walk the gauntlet of the gatekeepers, a series of bridge people who could lead me to the inner sanctum of the healers. Imagine my dismay at realizing that in order to advance in my quest, I would have to reveal who I was, where my family came from, what I was seeking, what I intended to do with the gift of their knowledge, and what I needed to heal within myself. If I made it past the gatekeepers and was judged to be of pure heart and intention, my team and I would be permitted to proceed with the work and I would be allowed to state my case to the master healers.

The more I was willing to shed my self-consciousness, my fear of being exposed, or my presentation of who I thought I should be, the more I learned from the people I got to know. As much as I wanted to be open, however, I truly did not wish to speak of my own healing heritage. And yet this was the one thing that, in the end, opened greater doors to deeper dialogue. I did not want to reveal that my great-grandfather was a blind man who could see the past and the future, and my aunt channeled deities to heal people, nor that this aunt had told me I had the gift of healing and was being tested. My mother funneled her healing abilities in a perfectly acceptable form: she became a registered nurse, and my brother, following in her footsteps, became an anesthesiologist. I had greater confidence in my filmmaking abilities than in my healing abilities. Rather than becoming a healer, I decided I would best serve the greater good by making a documentary about healing and spiritual traditions.

I found myself the reluctant heroine, not in comic-book terms of having excess courage or superpowers, but in terms of being propelled into the everyman's or everywoman's path toward exploration and discovery as outlined by mythologist Joseph Campbell. It is only now that I understand I was the unwitting protagonist swept up by an archetypal heroic journey in which fate cast and directed her. In looking back, every step that was presented to me could not have fallen more perfectly in place had it been scripted by a Hollywood writer—from hearing the call to adventure, crossing the threshold from the ordinary into the extraordinary world, meeting mentors, facing tests and trials, seizing the sword, and returning with the elixir. I did it not with full abandon but always holding on to doubt and questioning what I was doing. I wanted to make this story about the healers, the fading traditions, the making of a documentary film—anything but about myself.

Yet, if I was not sure of what I was doing, I was at least willing to go along for the ride. I practiced talking story, and in doing so, I was able to have a deeper understanding of what it means to be a shaman, medium, doctor, teacher, and healer and what it means to heal. I learned about reciprocity—for everything I wished to receive, I had to be willing to make an offering. I learned my job was not so much about preservation—capturing something as it is and keeping it in stasis—but more about regeneration—turning loss into life, death into renewal. I learned that medicine from one culture, no matter how foreign, could benefit people of another culture if its use could be recontextualized with meaning to those who would receive the remedy. I learned that indeed we are in danger of losing large chapters of our collective physical and spiritual pharmacopoeia, but that it is possible to transform ancient practices into applications for the modern world. And I learned that like talking story, unlike storytelling where there is a clear beginning, middle, and end, the path to the finish is not clearly defined, for there is still opportunity to discover, to recover, and to change the foreseeable outcome.

My friend Pablo Amaringo, a retired Amazonian shaman, said as we walked through an area of the rain forest that was destroyed by logging, "Cutting down a tree is like burning a book before it has been read." Although we may not be able to stop the fires, my hope is that we at least open the book, become aware of what we are at risk of losing, and perhaps find a way to generate something new with the seeds of what remains.

* * *

CHAPTER 1

Connectivity

I put the mala beads to my nose and inhale the sweet scent of sandalwood. As I put them around my neck, I think of the Tibetan Buddhist monk who'd taken them off his own neck and given them to me. In so doing, he'd passed along to me all the mantras and intentions of compassion he'd infused into them. It has been nearly a decade, and the cords of the tassels are frayed and the brightness of their gold and red faded, but the power of protection that emanates from them is never diminished. I say my prayer: "Mother, Father, Spirit, God, allow me to be of greatest service to the one before me. Allow her to receive the strength, courage, and healing she needs to stay on her path of highest good. Allow any energy that is appropriate to come through me to do so at this time. Allow anything that no longer serves her to be released. Thank you for allowing me to do this work."

I put the mala beads to my nose and inhale the sweet scent of sandalwood. As I put them around my neck, I think of the Tibetan Buddhist monk who'd taken them off his own neck and given them to me. In so doing, he'd passed along to me all the mantras and intentions of compassion he'd infused into them. It has been nearly a decade, and the cords of the tassels are frayed and the brightness of their gold and red faded, but the power of protection that emanates from them is never diminished. I say my prayer: "Mother, Father, Spirit, God, allow me to be of greatest service to the one before me. Allow her to receive the strength, courage, and healing she needs to stay on her path of highest good. Allow any energy that is appropriate to come through me to do so at this time. Allow anything that no longer serves her to be released. Thank you for allowing me to do this work."

Suddenly that old familiar feeling comes over me. My heart feels like it's going to explode and I am filled with a sense of well-being—like the passion of falling in love. I shift from seeing the furnishings and walls around me to seeing into another place and time. My hands begin to shake and I place them on my patient's head. I feel myself pulling out mental constructs that no longer serve her: "I'm not good enough," "I'm not supported," "I can't be who I really want to be." I lay my hands on her heart and tears begin to seep through her closed lids. I see so many disappointments. I move my hands to her lower abdomen and see invaders—those who did not hold this space as sacred. I cut the cords between her and them. Lighting the stick of palo santo, a sacred wood from Peru, I blow a cleansing breath into the top of her head, filling her with light and love. I run the wooden mallet around the lip of a Tibetan singing bowl; it evokes the tones of the heart as it vibrates. When she sits up from the healing table, she tells me, "I feel so full and yet so light."

I reply, "This is you without all the baggage. Remember this feeling." As we sit on the couch, I share what I saw while she was on the table, and she confirms a history of abuse, a string of heartbreaks, and multiple problems with her reproductive system. She adds that despite being successful in the corporate world, she never feels good enough, so she's driving herself, her marriage, and her soul into the ground. She wants to know another way of being. She is ready to learn and heal. And then she asks me, "How did you do it? How did you go from being in the film industry and working in high-tech to being a healer?"

Although it has been years since I accepted this as my calling, it's only now that I feel I can answer with clarity. "It was identity theft," I answer. "I had to lose my sense of who I was, or thought I was supposed to be, in order to connect with my authentic self."

Stay tuned for more exclusive excerpts, and read our sneak peeks of other female-penned books here.