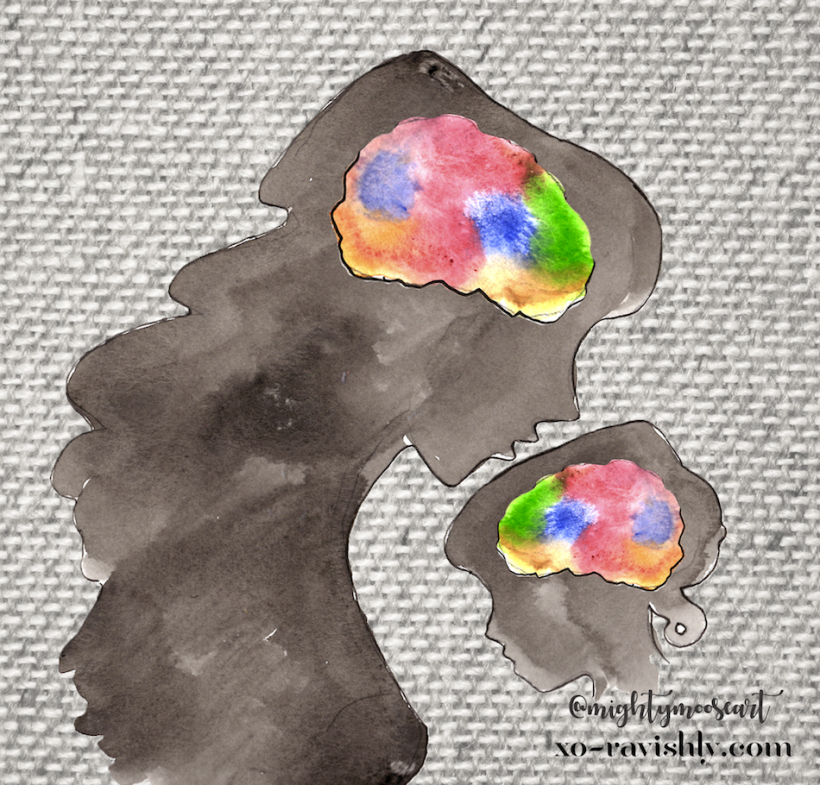

Image credit: Mariah Aro Sharp @mightymooseart

Being a mother is hard.

Being a mother navigating mental illness is hard.

I don’t know if navigating mental illness has made parenting harder for me than it would have been otherwise. I do know that having a mental illness that is wound into my DNA, means that I might someday be navigating my children's’ mental illness.

I did not think about this before I had them. I don’t know if I’d have done it differently if I had.

This is a thing you’d think someone would consider really carefully before procreating, but I did not. I was 19 when I got pregnant the first time. I wasn’t treating my own mental illness. I was still calling my mom’s mental illness alcoholism because being an alcoholic is somehow better than being crazy.

So I didn’t think about it much.

Until Kelsey was born. After she was born, I fell headlong into postpartum depression, where I stayed, trapped in the quicksand of sadness, my feet barely moving back toward joy, for a good long while. It was in the quicksand that I started to think I might be like my mother; it was there, that I began to think that maybe her darkness was also mine.

And then the worry came, bringing with it 20 years of memories. Memories of drunken boyfriends in and out my mom's bed, beer cans littering the kitchen, manic organizing, memories of moving and moving and moving again, of stepfather after stepfather, step-sibling after step-sibling.

And with that worry, came the watchful eye.

Babies cry — sometimes a lot. Toddlers have tantrums. Little kids scream at you “YOU’RE NOT MY MOM ANYMORE.” Teenagers tell you they hate you.

This is normal.

But, when you're a mentally ill parent, there is a seed planted, one that is being watered by every mood shift. Is this the one? Is this the first glimpse into your child's mental illness? Is this typical teenage pubescent nonsense? Or are you staring down the DSM, just waiting for a diagnosis to jump out?

I don't want to say that my mom "gave" me bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder isn't something given, not like gift on your birthday, not neatly wrapped and topped with the big pink bow. There is no neat wrapping. There is no bow.

No, it's more like something that just happens. You “get” it from your dad or, as in my case, your mom. Or it comes to you from your great aunt but via your parent’s chromosomal expression. One day you're just an average person, maybe with mood fluctuation that seems within reasonable limits, and the next day you've got a psychiatrist and a patient file full of the diagnostic codes for whatever thing the psychiatrist has decided you have.

My mom didn't “give” me bipolar disorder, but I did get it from her. Maybe she got it from her mom or her mom's mom. Maybe you can follow it back, all the way to England or Ireland or someplace on that side of the world. Maybe you can trace it 200 years to somewhere the grass grows green, and the mentally ill are either living as an eccentric artist, committed, or dead.

My kids won't have to do any genealogical research. They can track their mental illness right to the source, without ever leaving the small central California town we've lived in almost all of our lives.

They can follow the trail of mess and medications right to me, their mother.

A woman emailed me once and told me she loved my writing about parenting with mental illness. She told me that I'd given her “hope” that she could become a mother, manage a family. She asked me if I ever worried my children would “get it,” like “it” is diphtheria or measles, something you catch if someone sneezes on you.

She asked me for advice.

What advice can I give to a woman who wants to create life without destroying it in the process?

What do I tell someone who wants to know if I “worry my kids will get it?”

Yes. I do. I worry. Some nights, after I’ve taken the last handful of meds and done my progressive relaxation, I lay awake with worry that they will get it.

I worried when my first baby had colic. I worried when my second baby started acting like I did as a child — a pendulum of temper and sugary sweetness. I worried when my third child accidentally crushed our tortoise — did he do that on purpose? (No, he just stepped on it.)

I worried, in my second marriage (and my second time around the toddler block), when my fourth child became anxious and withdrawn. And then again when she was finally diagnosed as selectively mute.

I worried with my fifth child when he started to act a lot like my second child — the first one of the five that I thought might “get” it.

I worry every day, to some extent. Every time I swallow another handful of pills, every time I resent those pills for existing, and my mom for “giving” it to me, every time a symptom sneaks past a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Every time, I worry one of them will get it.

When I was finally officially diagnosed, I sat with my husband and older kids around our seven-foot dining table on Spaghetti-Thursday and told them I was bipolar. I told them because I believe they deserve that knowledge. I told them I believe I owe to them what my mother never gave to me, the truth about what they might inherit.

My oldest daughter, Kelsey, cried while her oldest brother, Sean, sat silently. It was Owen, the one who used to worry the sun would burn out, the one that's lost sleep over the idea of death and heaven and what happens when we die, that seemed most concerned, asking me finally, “What are the chances that one of us might get it?”

Forty percent is not the answer you want to give to your three oldest children — all of them on the possible precipice of their first manic break. Forty percent is not the answer you want to give, as you watch them watching each other, knowing this means one of them will one day wake up crazy, wondering which one of them it is. But 40% is the truth. And the truth is, one day you will be faced with taking one of them to their first psychiatrist appointment in a lifetime of psychiatrist appointments.

I told them the truth, because no one told me the truth, and the lie hurts worse. The truth would have led me to treatment, but instead, the lie took me on a rollercoaster of debilitating sadness and terrible decisions.

I don’t want that for them.

What I want for them is a world where saying “I’m bipolar” doesn’t mean anything more than saying “I have diabetes” or “I have a weird thing that makes me afraid of tiny holes (trypophobia, it’s real). I want a life for them that includes treatment and management and doctors who know what they are doing, and partners who know who they’ve married.

I want for them, a world that understands mental illness so well, with so little antipathy, that they won’t have to worry about their kids “getting it,” because “getting it” is just a thing that happens, not a life sentence of misery. I want them to know that their children “getting it” is no one's fault. I want them to know that “getting it” only means part of their parent is wound into their DNA, and that none of it is wound into their worth.

![Photo By Dr. François S. Clemmons [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](/sites/default/files/styles/profile/public/images/article/2019-06/Mr.%2520Rogers%2520%25281%2529.png?itok=LLdrwTAP)