You can be a strong heroine without being a tomboy.

Cinderella used to be one of my least-favorite fairy tales, and the animated Disney "classic" irritated me, even as a little girl. Coupling the repressive and dorky 1950s aesthetic with a story about a bland and spineless girl who neither stands up for herself nor gets to know the prince who falls in love with her (seemingly only because she's a good-looking unknown) never struck me as particularly charming.

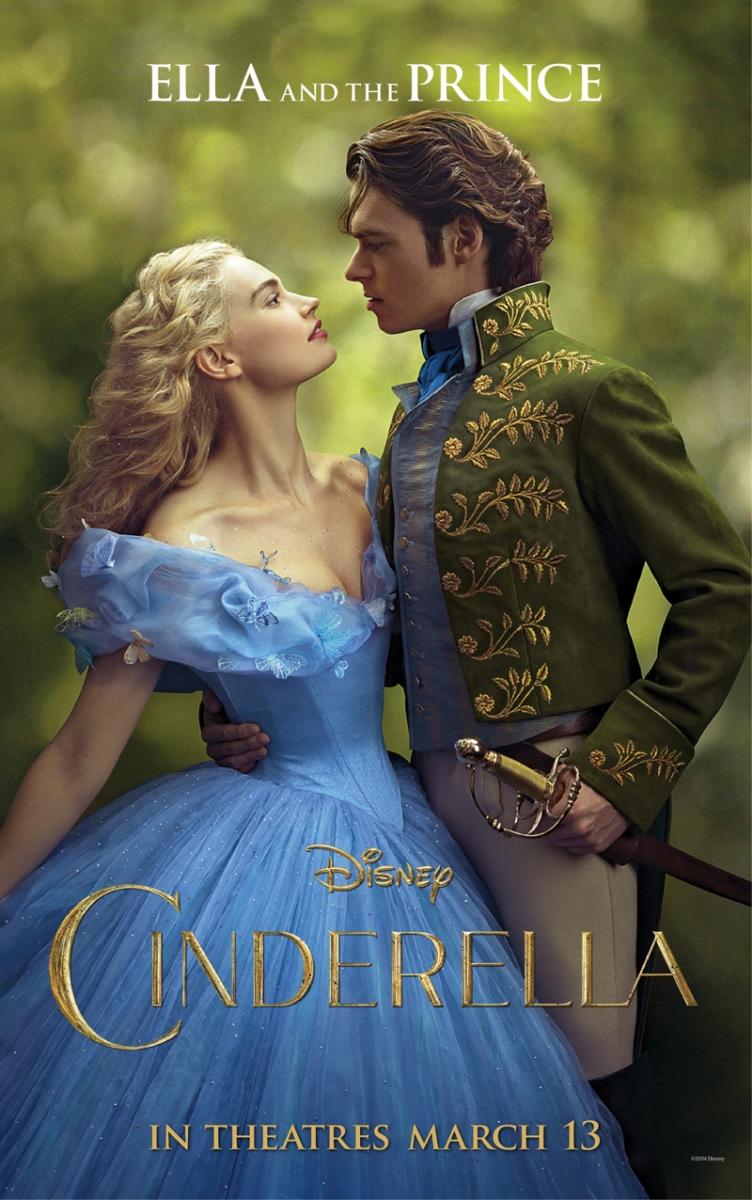

But I found Kenneth Branagh's recent live-action adaptation of the story completely delightful and would like to defend it against certain criticisms floating around the web of late.

Generally speaking, the new Cinderella has been a critical and commercial success, but some writers have criticized Cinderella's passivity as a character, to the extent that Branagh had to defend the film as not being about "a passive victim waiting for the guy." True, the film is a good deal less antiquated than the animated flick—but there's only so much you can do with a story about a subservient, docile, pretty young woman who can only escape her dismal living situation when she meets her handsome prince.

Since the original Cinderella came out, times have changed. There's a reason the tatted-up, frank, tough Lena Dunham is a synecdoche for much of her generation; modern-day feminism prizes independence and strength. Meanwhile, Disney has made significant strides in its depiction of female characters. In Brave, Merida is ultimately more interested in reconciling with her mother than in finding a husband; in Maleficent, Angelina Jolie's complex protagonist grapples with PTSD after what's been interpreted as a rape or clitorectomy.

Narratives like these are a huge relief and a step forward. But they don't mean the more old-fashioned Cinderella isn't, in her own right, a feminist role model.

There are other kinds of bravery and heroism besides the kinds involving fighting instruments and fighting words, and you can be a strong heroine without being a tomboy (however you define tomboy). Cinderella reconciles us to the original tales the revisionists fought against, while still showing us a strong-willed heroine with a backbone—if one not immediately apparent.

As Ella's sweet and affectionate mother is dying of some mysterious illness, she tells her daughter that the girl has more kindness in her little finger than most anyone else, and advises that she, above all else, "have courage and be kind." At first glance and listen, that seems like pretty frothy advice, bereft of meaning or substance. What kind of superpower is that? Ella's gift won't be martial arts or fireball magic . . . but that she's nice?

Yes, and that's where the courage part comes into play.

If the question at the heart of viewing Cinderella is, "But why does she put up with it?" or, "Why not just pick up and leave?" then we get the answer in the dying mother's advice.

It's hard to do the right thing. And it's really hard to be nice to those who treat you badly—nice like you mean it, not obsequiously so with an agenda.

The only way Ella feels she may honor her parents' memory and the things and home they held dear is to treat those her father chose to ally with respectfully. That also means taking care of the house that once belonged to her parents (and which now actually belongs to her). It means not speaking ill to and of the people her father made their family and brought into this beloved home.

If Ella were to fight back with either words or swords or both (a la Inigo Montoya), that would make complete sense, and we would support that. But to her, doing the right thing means treating her adoptive family well and not gainsaying their requests.

She also knows that they have the power. If she fights back, they will kick her out of her own house, and she will never have access to it again.

It's difficult to overstate the power of constant negative reinforcement. You tell someone she's stupid, ugly, or useless enough times, and even a stalwart person will likely on some level believe it and begin to incorporate that into her schema. Couple that with an already weakened emotional state from someone who needs your love and attention, and you may be able to change someone's entire identity and self-perception.

The film depicts the stepfamily telling young Ella that she is nothing and deserves the treatment she gets, and after awhile she begins to believe it. That makes fighting back even more unlikely. If she believes this is what she deserves, how could she fight back . . . and why would she do so?

By showing us conniving jealousy and Ella's kind and patient reaction to it—rather than showing her exact revenge, a la Emily Thorne, an immediately satisfying but ultimately depressing response—we're supposed to take away a different lesson: Being good is one way to lessen the world's evils, including those evils tied up in the kind of systemic oppression 18th-century women like Ella faced.

The grown-up Ella learns not to let it all get to her, after all. Toward the end, when she starts calling herself Cinderella instead of Ella, we see she's appropriating her oppression. This is no mistake on the part of the scriptwriters or some cheap nod to the fairy tale's English name. It's her way of taking on her abused identity as a badge of bravery and survival, and a means to transcend her mistreatment. So powerful is she that she doesn't punish her stepfamily, but takes the high road to forgive them.

"I forgive you" are, indeed, the last words she utters to those who have so ill-used her. And that takes a strength of will in which many women can find inspiration.

![By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](/sites/default/files/styles/profile/public/images/article/2019-06/Bell.png?itok=gWp6s_Y0)