If sugar is the problem, then why stop at sugary drinks with this soda tax? Why isn’t there an éclair tax or a tiramisu tax?

I came out of a 4-day fever dream accompanied by major coughing grossness last Thursday, and all I wanted was those precut pineapple spears from Trader Joe's and a mocha frappe from McDonald’s. It was the perfect setup: McDonald’s is 3 storefronts down from Trader Joe’s at the mall down the street. I was still on the mend, and in fact was sweating during most of the drive to the aforementioned mall, having had to break a fever the night before by sitting and watching all the Bob’s Burgers Thanksgiving episodes (I find the Thanksgiving themed ones the most comforting for some reason) with a wet towel on my head for four hours.

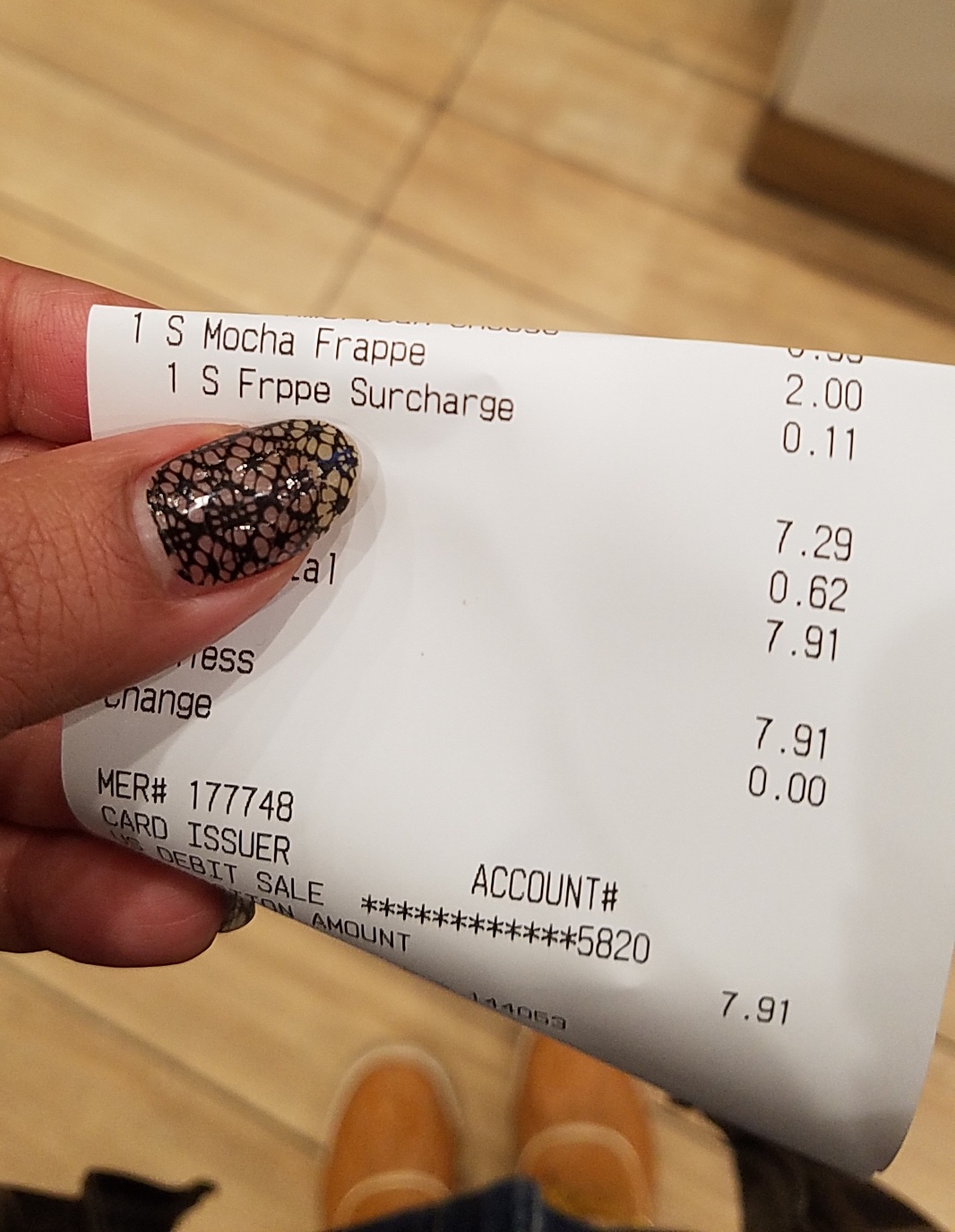

Pineapple acquisition went off without a hitch, and then it was time to get my frappe. As I got to the front of the line, I saw little white signs everywhere alerting me to the fact that there is a sugary drink tax and that I would be charged an extra eleven cents for my icy cold, comfortingly sweet coffee-flavored beverage. And it gave me a feeling.

Namely, it felt not at all coincidental that the first time I encountered this tax was at McDonald’s, a fast food restaurant that makes the “respectable” classes cringe.

Other people have written about the ways that a “sin tax” on soda has largely been championed through childhood obesity and diabetes fear-mongering rhetoric. I’d like to talk about the history of sugar, the disproportionate concern for the way that poor people consume sugar, and the ways that this kind of tax — and anti-fat rhetoric in general — targets poor people implicitly through the obfuscating language of health and economics.

If sugar is the problem, then why stop at sugary drinks? Why isn’t there an éclair tax or a tiramisu tax? I think the answer is simple: consuming sugary drinks is considered something that poor people do.

I looked up the official argument made by proponents of the sugary drink tax in San Francisco, and it read, in part: “Sugar is a toxin that goes straight to the liver and other vital organs.” There’s a large theoretical leap between the statement “Sugar is a toxin” and the conclusion that sugary drinks needs to be taxed. That’s because there’s a silent and problematic induction process happening, where “combating” sugar isn’t as much of a priority as taxing the consumption of soda. In short, if sugar is the problem, then why stop at sugary drinks? Why isn’t there an éclair tax or a tiramisu tax? I think the answer is simple: consuming sugary drinks is considered something that poor people do.

You Might Also Like: The "Fat Tax" At Spas & Salons Is Discriminatory And Unacceptable

I looked back at one of my favorite books on the subject of food and its connections to class, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History by Sidney Mintz. Mintz goes into the ways that certain foods and styles of consumption are aligned with people’s identity and play into the creation of hierarchy. He writes, “Food choices and eating habits reveal distinctions of age, sex, status, culture, and even occupation.”

The book offers (in my nerdy opinion) a riveting account of how sugar transformed in the UK from a luxury item enjoyed only by the very wealthy in the 1600s to a staple in the diet of every English person by 1800. The transformation of availability occurred when sugar cane, sourced from the Caribbean with slave labor, was replaced by sugar beets, which could be cheaply grown in Europe. The price of sugar dropped drastically with the introduction of sugar beets. Sugar became known as a yummy and cheap way to add calories to tea, which was a boon for the laboring classes who worked hard and needed easy and affordable energy.

The wealthy were scandalized by the audacity of poorer people adopting an elite comestible.

Not long after that, a reformation campaign was launched by a man named Jonas Hanway. He wrote “An Essay on Tea,” in which he argued that tea hurt society because it was foreign (wrong), suggested that sugar — which often accompanied tea — caused scurvy (also wrong), accused the laboring classes of being wasteful and extravagant for wanting sugar in their tea (wrong again), and suggested that tea should carry a tax (sound familiar?).

Important Context: No one like Jonas Hanway spoke against the fact that the sugar cane trade relied upon slavery, which was immoral and led to the death and destruction of thousands of people’s lives for the acquisition of an elite treat. The problem of morality only arose when poor people began putting that treat in their tea.

The sugary drink tax I got on my frappe is an extension of this very history.

The interesting thing about sugar is that it’s not tax-worthy or particularly problematic in all its forms. As Mintz pointed out, there’s a hierarchy around how sugar is consumed. There are “respectable” and acceptable forms of consumption, like gourmet desserts. And there are less respectable and less acceptable forms of consumption, like soda. The double standard is obscured through explanations about how this is a health and/or economic issue, plain and simple. (e.g., In the official argument document for the sugary drink tax in San Francisco, it states: “Scientific evidence demonstrates that there is a direct link between sugary drinks and diseases… driving up healthcare costs for everyone. San Francisco pays over 87 million dollars for direct and indirect costs of diabetes.”) The double standard is glaringly absurd, but grounded in a long history of selective regulation and bigoted attitudes.

In the same way that fatphobia has become a hidden way to pathologize poor people, so too does the taxation and regulation of certain kinds of sugar consumption belie the ways that health and economic initiatives can seem innocuous (or even pragmatic) but, in fact, are selectively punitive.