Our identities are so much more complex than black or white. The real juicy bits are in the gray, where we explore our predilections for Jane Austen AND Alice Walker. It is where we discover that we prefer Jill Scott’s music to that of Taylor Swift. The gray is where we allow ourselves to be more than just stereotypes.

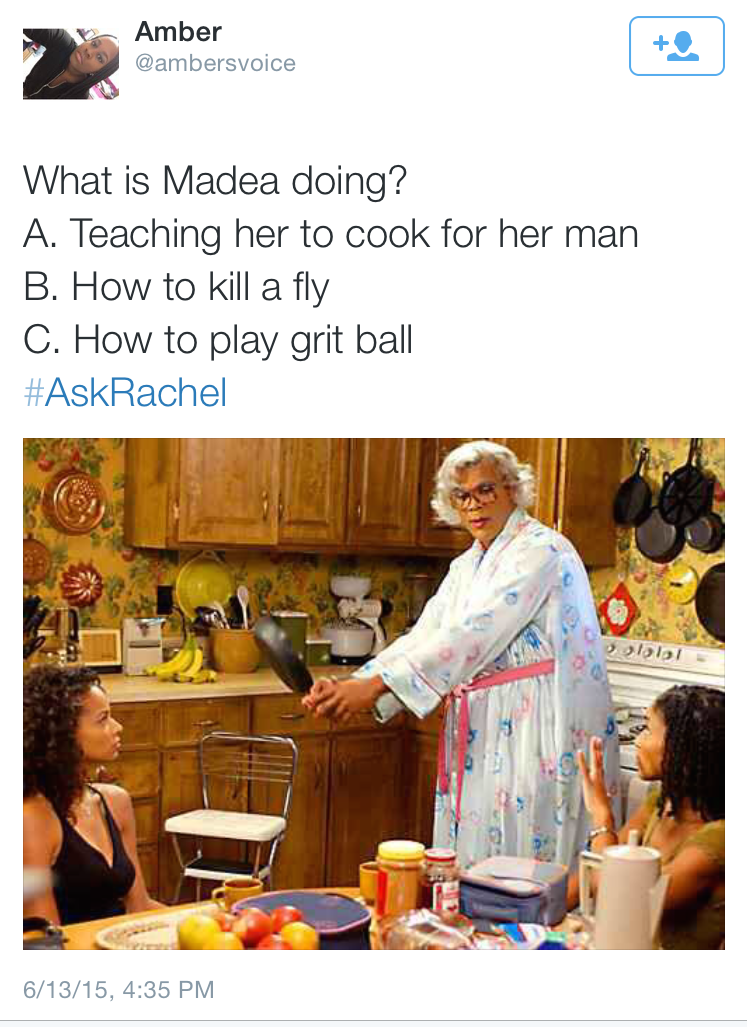

When I first read about Rachel Dolezal pretending to be a black woman for a decade, I was angry and disgusted. I called out her blatant cultural appropriation on my Facebook page, and commentaries of all kinds ensued. I spent a good part of my day on Black Twitter, reading the reactions, retweeting the ones I thought most reflected my feelings. The hashtag #AskRachel became the source of many memes, like this one:

The memes were meant to test Rachel’s knowledge of blackness, and at first I thought they were hilarious. But after much thought and conversation with others, it became problematic for me. It suggests that all black people have the same cultural experiences because of the color of our skin, and that’s simply not true.

As I engaged in further conversations with all sorts of people, it made me also think about long-standing black appropriation in this country. From jazz to hip-hop to Bantu knots on white models in a Marc Jacobs fashion show, this country has a history of white folks appropriating practices and art forms that don’t belong to them.

And if we look at the phenomenon of passing, which folks of color used as a survival tactic, it is also, in a sense, appropriation. But the motivations behind them are very different.

So the question I ask is, when does cultural appropriation go too far?

In answer to this question, I look to some personal experiences.

I have non-black friends of different races who identify very closely with regional black cultures because of their upbringing in those communities. Their tastes in music, art, and romantic partners were are all influenced by their surroundings. Some of them even code-switch to using black folk speech in certain circumstances. Their affinity for black culture is undeniable. Do we consider this appropriation? Or is it identification with the predominant culture in which you grew up and respect?

Similarly, I have black friends who grew up in largely white neighborhoods and went to mostly white schools. Their experiences were completely different. They listened to AC/DC and had crushes on blue eyed, blonde haired, white boys because that’s what they were exposed to. They were obligated in some ways to appropriate white culture as a means of fitting in. Is it fair to delegitimize their experiences because they didn’t learn the electric slide or groove to New Edition?

When I was a kid, the insult of choice by black kids at school was to call me an “Oreo,” the suggestion being that I was presenting as black on the outside, but that my cultural expression was white. And of course, the obvious critique was that, as a mixed race person, I didn’t fit in anywhere. The impact of those messages took me many years to unpack.

My point is that there is no one way to be black (or white, or brown, etc.). Cultures are far too diverse and nuanced to be monolithic.

So, is being black about race or culture?

Anthropologist John H. Relethford says race is a “culturally constructed label that crudely and imprecisely describes real variation.”

Word!

Our identities are so much more complex than black or white. The real juicy bits are in the gray, where we explore our predilections for both Jane Austen and Alice Walker. It is where we discover that we prefer Jill Scott’s music to that of Taylor Swift. The gray is where we allow ourselves to be more than just stereotypes.

Race, like gender, is a social construct meant to oppress certain groups and empower others. But culture is much more fluid than that, which is why we resonate with certain groups more than others. And I suspect Rachel Dolezal felt an affinity for black culture.

Her intention, which presumably was to try and experience the oppression of black folks, was not a bad one. I can see how a social experiment like this could be eye-opening for someone who doesn’t see the injustices done to black people in this country.

But 10 years is more than an experiment. It is a distortion of reality at the expense of the real experiences of an entire group of people.

I am definitely disturbed by the extent to which Rachel Dolezal lied. Pretending to be the victim of a racially motivated hate crime is a betrayal to folks of color who have genuinely experienced it, and did not have the choice to go back to the privilege of being white. It reduces the credibility of black oppression, which is unforgivable.

These tweets only confirm my suspicion that Rachel Dolezal is probably more unwell than she is racist:

Dolezal had been culturally appropriating for 10 years in the name of advancing black people. What’s so frustrating about this case is that she could have been just as effective, if not more effective, had she been herself. She could have continued painting black subjects and teaching African-American studies as a white woman. I think she took being an ally completely out of context.

For the folks who defend her actions, I remind you that she always had the choice of going back to being white at any point. A choice real black folks don’t have.

And while her hair game may be dope, this Facebook selfie causes my blood pressure to rise. The natural hair movement is one close to my heart. Seeing these photos undermines my experience and that of other black women who have chosen to go natural for a multitude of reasons. Really, Rachel?

Not to mention that someone who compares herself to the likes of Rosa Parks on social media is unwell. Her story is definitely an anomaly, but one we can learn from if we’re willing to ask the right questions, look at the spectrum of appropriation, and what we consider acceptable or unacceptable. Taking on a culture is one thing. But taking on a phenotype in the name of solidarity is perverse.

I think this story has the potential to create larger conversations about the difference between race and culture. It can remind us that choosing our own multi-faceted identities is the key to our diversity. And it is a cautionary tale of how not to appropriate the successes and the struggles of others.