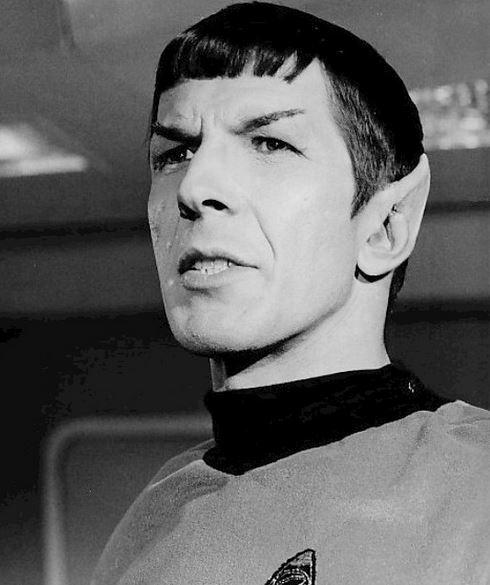

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

With the recent death of Leonard Nimoy, it's a good moment to pay tribute to his most famous character—Mr. Spock, one of the great sex symbols of his day.

True, Spock isn't usually thought of as a sex symbol exactly—but the many women I've known who've loved the show loved it, as often as not, in no small part because Nimoy in those ears prompted not logical algorithms, but decidedly earthier palpitations. It's no accident that the first great rush of m/m slash fan fiction in the U.S. focused on Kirk/Spock. Though William Shatner's Kirk was always presented as the swaggering lothario, Spock's eroticism was at least equally potent, not least for being so deliberately and elaborately buried.

Spock was probably Star Trek's most powerful and successful character precisely because he embodied aspects of idealized masculinity which weren't, and still aren't, given much pop culture expression. Kirk, the dashing risk-taker, is the more typical male hero, a boisterous man's man of action. But Spock's character is, in its own way, every bit as stereotypically masculine. He is super-strong, both in the sense that he has more-than-human physical prowess and endurance, and in the sense that he is super-stoic. He exhibits no emotion; he is calm, rational, logical, unflappable. His lack of affect is not based in cruelty, though, but in kindness. If he's distant, it's not because he does not care, but because he refuses to impose his needs or desires. Spock's single most iconic moment, the death in Wrath of Khan, neatly sums up his character as a whole. "The good of the many outweighs the good of the one," he declares, exposing himself to on-the-job radioactivity to save the ship and his friends—a very gendered sacrifice, considering who typically suffers from work-related fatalities. Spock's own needs and desires always come second; without bitterness or anger, he does the manly thing, putting his (dangerous) job and duty above his personal safety.

This combination of strength and self-abnegation is only made more appealing by the repeated assurance, throughout the series, that it is self-abnegation. Spock's logic conceals seething, boundless passion. As with any number of romantic heroes, from Rochester to Christian Grey, power is only made sexier by the revelation of inner weaknesses and wounds. Star Trek loved to show Spock coming apart, the logical veneer torn apart by uncontrollable passion. The loss of control is, inevitably, figured as sexual.

In "Devil in the Dark," Spock mind-melds with the Horta in what Kirk declares a "terrible personal lowering of mental barriers"—a moment of emotional nakedness leaving the usual sober Spock yelling and quivering. "This Side of Paradise" is even more explicit; Spock gets shot in the face with an alien flower, which releases him from his logical prison. "There's no need to hide your inner face anymore," the heroine declares as flute music plays—a scene that nicely echoes the emotional payoff of many a romance novel. And, of course, there's "Amok Time," in which it's revealed that Vulcans periodically enter a kind of sexual frenzy. "It strips our minds from us. It brings a madness which rips away our veneer of civilisation. It is the pon farr. The time of mating."

Again, the whole point of the episode is to show the uber-controlled Spock losing control—whether that means having a tender moment with Nurse Chapel, telling his wife how he burns, or letting loose an ear-to-ear grin when he sees that Kirk is alive (one of those moments that no doubt has launched a thousand fan fics).

It's easy to see Spock's appeal as a masculine icon. He's strong but not violent (nerve pinches, not fisticuffs); respectful of personal space but super-empathic (what with all those mind-melds); responsible and safe, but with passionate depths. The recent films have made Spock more of an obvious romantic lead, but in doing so they've abandoned the delicate balance between repression and accessibility, stoicism and vulnerability, which made Nimoy's Spock so attractive.

That attractiveness, though, can also seem a little disturbing. If Spock is a kind of ideal, that ideal seems to be masculinity as repression. There's something appealing, Spock seems to say, about a man so divorced from his own emotions that he has to be shot in the face with alien flower spores in order to be able to say, "I love you." Spock's whole emotional life is one long act of self-sacrifice; love, hate, desire, all placed upon the alter of duty and workplace professionalism.

If Spock were real, he would not be a fascinating, powerful alien, but a seriously broken human being, radically and disturbingly disconnected from his own emotional life. That this improbable character has been so popular says something about Nimoy's charisma, and something about how ambivalent we are about masculinity, which is most sexy when severed from sex, and most admirable when most repressed.