Breaking the GAS Ceiling

To say Amelia Florence Behrens Musser Furniss led a colorful life would be an understatement.

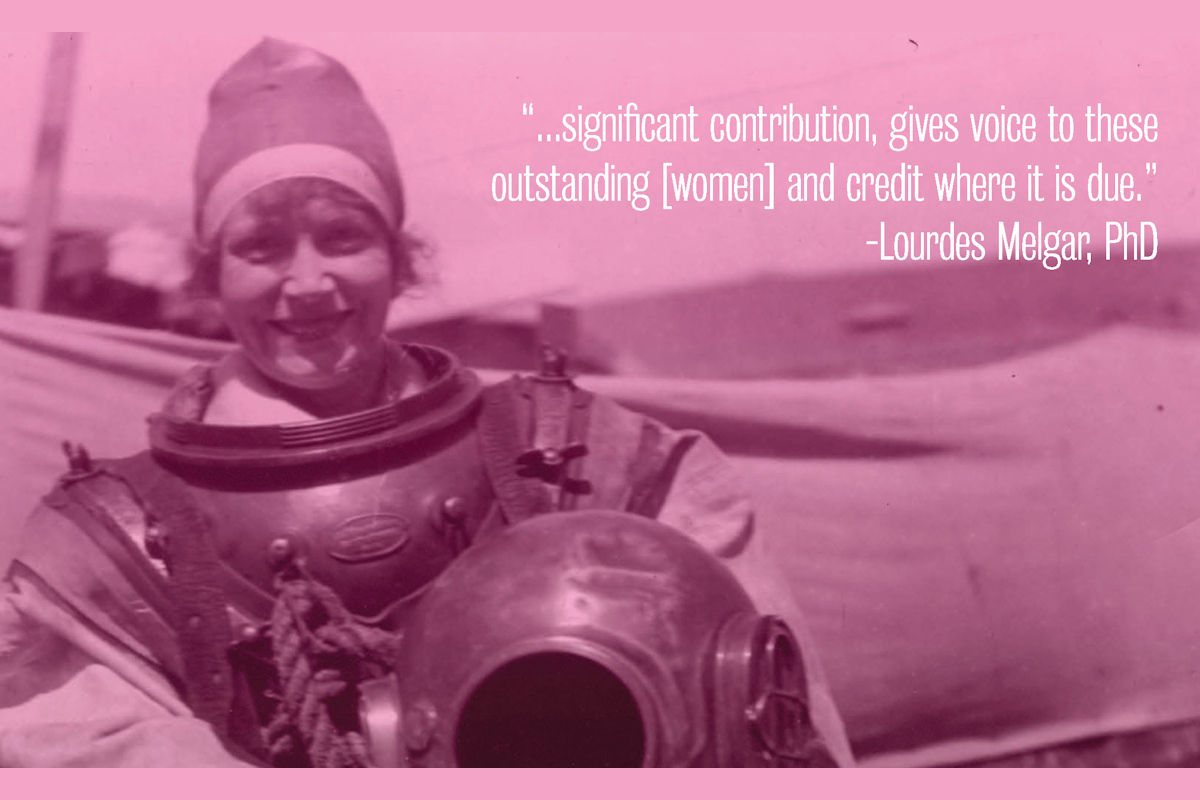

Born July 6, 1895, just one year before the discovery of Summerland oil field in Santa Barbara County, California, the site of the first offshore discovery in the U.S. from wells drilled from piers that extended out to sea, her father, Captain Henry Behrens of Denmark, ran a commercial diving business before the turn of the 19th century and a diving bell exhibition on the Venice Pier in California, and taught both Amelia and her sister, Dorothy, to dive.

In the Roaring Twenties and the era of the flappers, she was unpredictable, unconventional – and, yes, unflappable – seemingly up for any type of adventure. “The diving girl,” as she was often called, first made it into the newspapers in March 1913 when her marriage at the age of 17 was listed in the Los Angeles Times.

In an October 1921 newspaper article, you can fairly hear the annoyance in the (presumably male) reporter’s voice when he types, “If it isn’t one thing, it’s another with Florence Amelia Behrens Musser, woman diver. Florence Amelia manages to get on the front page of newspapers every few months.” He goes on to write about her latest “exploit” – a dangerous descent into a 162-foot oil well through 24-inch casing to retrieve some tools – as if it were a media stunt. Amelia had been asked – or volunteered, depending on the account – to attempt to retrieve the expensive tools when Captain’s Behrens’ size prevented him from going into the pipe.

A faded tea-colored clipping in Amelia’s scrapbook from the Venice Vanguard Evening Standard takes a different tone, with the front-page announcement of the triumph of the local “deep sea diver [who] has won a new record, unparalleled in the history of diving and underwater exploits.”

Months later, newspapers across the country were still running the story with the dramatic headline, “Sea Diver Fights for Life in Oil Well,” but none ran Amelia’s photo.

She made five dives over a period of three hours, in water 45 feet deep, setting an endurance record, but became wedged in the pipe on the final dive. By staying calm and keeping her wits about her, she finally was able to free herself. While the danger was real, a reporter for the Oxnard Daily Courier, writing in the sensational tone of the day, claims, “. . . she wondered whether she would ever come out alive.”

The story was even given a small mention in the Comment section of Petroleum Age. Referring to her as “Miss Behrens” (although she was married) and the “daughter of Captain Henry Behrens, sea diver” the piece opens with the line, “Believe it or not . . .” and ends by saying, “We say this story takes the cake.”

Was the incredulous tone because of the feat itself or because she was a woman . . . or possibly both?

Despite extensive press coverage, it seems there were those who had their doubts that a woman had accomplished such a coup. The Rig and Reel magazine ran a photo of Amelia formally dressed in a coat and hat wearing dark lipstick next to the caption “Somebody said it couldn’t be done – and so Miss Amelia Behrens did it.” It went on to say, “And others hinted that it wasn’t done, so we asked Captain Behrens to verify it – which he has done to our complete satisfaction.” The magazine printed Captain Behrens’ letter dated December 7, [year not given], in which he also wrote, “Amelia . . . is . . . perfectly fearless and has complete confidence in herself in whatever she does.” And with that stamp of authenticity, it went on to show the photo of Amelia, which Captain Behrens verified was taken that day, her slight, 5’1”, 118-pound frame encased in the 446-pound wet suit, along with an article detailing her record-breaking dive, retrieval of the tools, and timely escape.

As if record-breaking diving weren’t enough, Amelia also performed wing walking and stunt work in silent films, such as the classic Perils of Pauline. Grandson Noel Mark Furniss, Retired Air Force Chief Master Sergeant, Air Force Central Command, recalls how Grandma Mimi would answer his “inquisitions” and when he asked her about the hard hat diving and wing walking, she told him she had to do those things because the men couldn’t.

Excerpted from Breaking the GAS Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil & Gas Industry (Modern History Press; May 2019) by Rebecca Ponton. Available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other booksellers.

Breaking the GAS Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil & Gas Industry (Modern History Press; May 2019) is the result of author Rebecca Ponton’s desire to record and preserve a missing piece of the history of the offshore oil and gas industry, which is the role of women’s contributions to the sector.

The international petroleum industry has long been known the world over as a “good old boys’ club,” and nowhere is the oil and gas industry’s gender imbalance more apparent than offshore. The untold story, shared within the pages of this book, is about the women who have been among the first to inhabit that world, and whose stories previously have been a missing part of the history of the industry.

In the book, which has been said to read like a collection of short stories, Rebecca has written “condensed biographies” of 23 women of various nationalities, ages, and positions within the industry, many of whom have achieved “firsts” in their fields.

It is Rebecca’s hope that the book not only will help preserve history but serve as a written form of mentorship based upon the wisdom and insight of the women profiled within its pages.