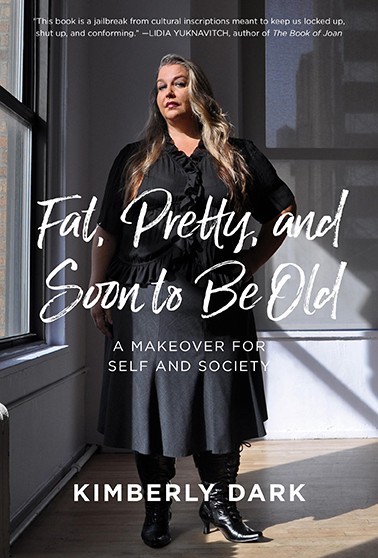

Photo courtesy of Kimberly Dark

We were thrilled to connect with Ravishly writer Kimberly Dark about her recently published book, Fat, Pretty, and Soon to be Old.

Fat, Pretty, and Soon to be Old is a moving, funny, and startlingly frank collection of personal essays about what it means to look a certain way. Or rather, certain ways. Navigating Kimberly Dark’s experience of being fat since childhood—as well as queer, white-privileged, a gender-conforming “girl with a pretty face,” active then disabled, and inevitably aging—each piece blends storytelling and social analysis to deftly coax readers into a deeper understanding of how appearance privilege (and stigma) function in everyday life and how the architecture of this social world constrains us. At the same time, she provides a blueprint for how each of us can build a more just social world, one interaction at a time. Includes an afterword by Health at Every Size expert, Linda Bacon.

Ravishly: You open the Introduction with, “This is not just a memoir in essays. It’s a call for radical cultural change.” What I love so much about this collection is that it is just that. I think many good memoirs do address larger cultural issues; they may not do as directly as this. Did you have this intention in mind when you first conceived of the book?

Kimberly Dark: I've been writing personal essays about social issues for so long that it seems normal to me. I have to remember that it's a unique thing. Mostly, a book about an individual's life is called a memoir. I understand that, and I'm happy for however someone connects with the book.

The thing is, Fat, Pretty, and Soon to be Old isn't a story of my life—it's a story of my appearance and identities, and wow, this is part of the point I hope to make: women are more than their appearance! To me, this is a collection of essays about social change. I mean, sure, they're using my life as an exemplar, but only because it helps me to tell interesting stories. Every story is about me, but I'm not the subject. The subject is how we reclaim our power as social creators and stop accepting a society where power and privilege are based on appearance hierarchy. That's a social error that's steering us all astray, and we can change that narrative more easily than we know.

Ravishly: In the collection, you confront so many cultural standards head-on, both in your personal relationship with them, as well as how they function within society. Did you find some aspects more challenging to confront than others?

KD: Here's something not everyone knows: When you start to look at the social context of your individual pains, challenges, and experiences, every possible topic becomes easier to discuss. Sure, I'm writing about things like incest, public humiliation, eating disorders, and social stigma, but none of us experiences those things alone. Social context means that I don't have to carry shame or pity as a result of my own experiences. When we understand (or at least are willing to investigate) the social context of our lives, difficult things still hurt, but they're no longer unspeakable. I find certain essays more difficult to write, but usually, it's because I'm trying to make a complex point easy to grasp. That kind of challenge is worth the effort.

Ravishly: What reader reactions have been the most surprising for you?

KD: This book discusses a lot of aspects of appearance and identity privilege—from race to gender to disability, size/weight, aging, tall-pretty-people privilege, and more. People's experiences relating to these things are definitely not the same, and yet, when it comes to the mechanics of oppression, they're sometimes analogous.

I want to reveal the hidden architecture of everyday privilege and oppression in meaningful ways. I hope to prompt action in everyday lives too. What astonishes me is how often people hear me speak or read from the book and go directly to questioning whether I should discussing fat with such neutrality. Isn't it unhealthy? (No, not inherently.) And what about the "obesity epidemic." (Hmm, it's a socially constructed moral panic. And a form of eugenics.) I think this 'what about FAT!?' response may be less common from those who choose to read the book, but because I do campus and other public presentations, the biggest freakout is still about fat. It's tiresome. It's sad. And it reminds me of how important these discussions remain.

Ravishly: What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received? What’s the worst?

KD: The worst? Ha! I recently wrote about this. One of my high school English teachers said I'd never be a great writer because I cared too much about message. Great writers only care about language, he opined—what a dimwit. Of course, releasing me from the burden of my future greatness may also have been a gift. I never for a minute, stopped writing exactly what I wanted to write.

Ravishly: What are you currently reading?

I just finished and enjoyed both Red at the Bone by Jaqueline Woodson and In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado. I'm reading Testo Junkie by Beatriz Preciado, and of course, one of my favorite books of last year (sociological, personal essays—woohoo!) was Thick by Tressie M. Cottom.

Kimberly Dark is a writer, professor, and raconteur. She has written award-winning plays and taught and performed for a wide range of audiences in various countries over the past two decades. She is the author of The Daddies, Love and Errors, and co-editor of the anthology Ways of Being in Teaching.